“Alice laughed: “There’s no use trying,” she said; “one can’t believe impossible things.”

— Alice in Wonderland

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was younger, I always did it for half an hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

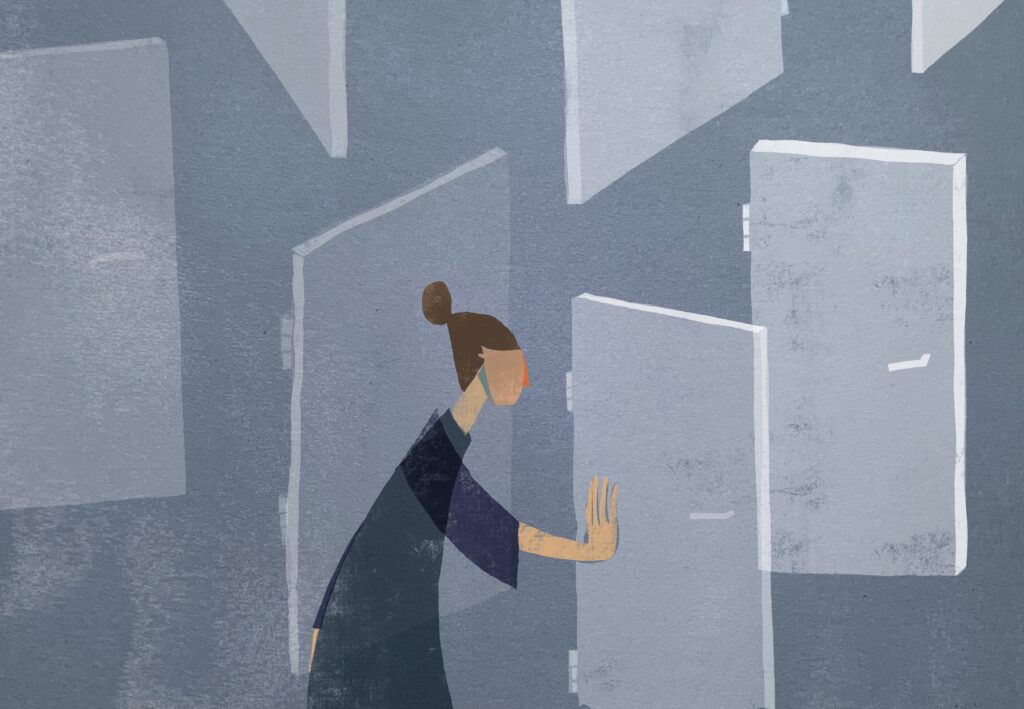

What skills do we need to face the challenges that lie before us?

We are beginning to have the kinds of conversations about learning to cope with the world that no longer focus on traditional forms of education, knowledge or skills, but on our abilities to cope with emotions like fear and uncertainty.

“Burnout is at an all time high, resilience is at an all time low – and our low tolerance for uncertainty is at the heart of it all,” the Uncertainty Experts tell us. And beyond just coping, we must also develop the ability to choose an appropriate course of action: what can we do that will actually have an impact?

Uncertainty can be a great motivator, as it is often through moments of uncertainty that our imaginative thinking can be unleashed. And imagination is the driving force behind all great social change.

Whatever may or may not have been achieved at COP26, one thing has become abundantly clear: our current governments and systems of governance are not fit to take us through the challenging times that lie ahead. We need revolutionary change and “industrial era governance won’t solve the problem it created,” warns Juha Leppänen.

One thing most of us can agree with is that the future is too important to be left to a small group of the global elite. However, most of us also feel powerless to actually influence change at the highest levels. So what can we do?

While reform is essential, it won’t come around quickly enough. Leppänen suggests that “[g]overnance is the missing link between individual empowerment, coherent transformations, meaningful policies, and action of sufficient scale,” and that in order to tackle the climate crisis, we need relentless conversations and experimentation.

And experimentation is the space where we play with impossible ideas. Most great social innovation of the past, like the welfare state, was once thought of as impossible. And crucially, they came about through processes of social imagination that harnessed collective intelligence. They were not led by one institution or one sector of society, but people from all walks of life, from institutions to local clubs to utopian writers.

In a conversation on social imagination, Johanna Koljonen introduces it as “the ability to believe things about the social world that may currently feel quite unlikely or even impossible to achieve.”

And what is so beautiful about the concept of social imagination, Roope Mokka explains, is that “it offers an alternative to bottom up or top down as a dichotomy.” But, he explains, there are no ready answers, we’re going to have to craft those experiments and we are going to need guidance and investment from the top while also involving people who are subject and object to these ideas.

Unfortunately, most institutions that were once created to implement these impossible ideas, no longer have the ability to think imaginatively. In fact, in most of our sectors, using imagination is seen more as a distraction than a foundation of our strategies.

The key, Cassie Robinson says, is that we have to understand what the collective imagination can achieve which the individual can’t. And while everyone has an imagination, being able to access and use it effectively, in communion with others, is something that requires practice, skill, and support.

But this work can happen through collaboration, if the purpose of coming together in the first place is for social imagination. And it is already happening in other sectors we can look to for inspiration, such as technology and the arts.

So, if we turn back to the failure of COP and the widespread disappointment, maybe we have to imagine new institutions that centre intergenerational equity to lead us into the future? Perhaps the skills we should teach our children alongside solidarity and civil disobedience, should include working with – not against – fear, uncertainty and the impossible.

In the words of physicist Chiara Marletto, “declaring something impossible leads to more things being possible.”

So what impossible ideas are out there waiting for us to begin to play with?

Words, Veronica Yates and illustration, Miriam Sugranyes

For references, resources and further reading, visit our inspiration page.