“I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking.”

— Henry David Thoreau

“The history of walking is everyone’s history,” Rebecca Solnit writes in Wanderlust. And like so many of our other basic bodily functions – from breathing, to speaking, to sleeping – human bipedalism is a practice, which, if we have the ability, we must never seize to preserve, reclaim, protect and cherish.

Modern technologies entice us with faster and cleaner ways to move around without the use of our feet, and as Solnit remarks, the time we may spend walking is increasingly seen as time that needs to be made productive.

But walking is more than a mere form of transport. It can be a performance of sport, like reaching the peak of a mountain or practised in order to keep healthy, both physically and mentally. A lot of research extols the benefits of walking for healthy brain function, for example.

It is something we can do in communion, whilst holding conversations or meetings, like the peripatetic philosophers for whom walking extensively was a habit. Aristotle, for example, would often teach while walking.

It is also a form of protest, which has been practiced for centuries. Beyond simply gathering in groups, marching has been used as an act of liberation for those who were barred from doing so, for example, women and children (who are still not allowed to do so freely in parts of the world).

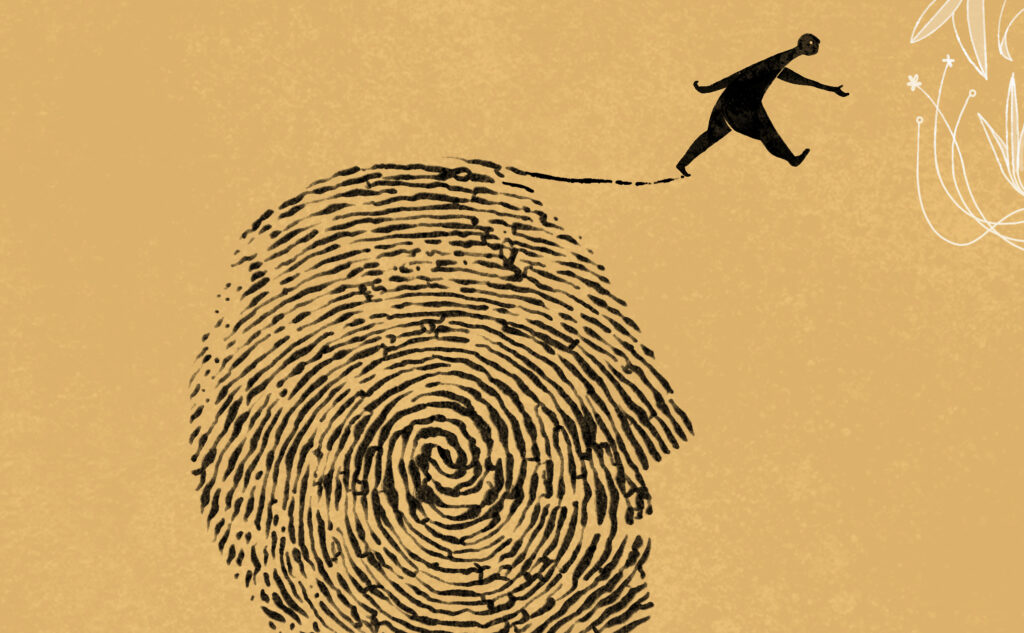

Walking is also often a solitary practice: we may walk to clear our heads, as meditation, or simply to connect with nature. Walking is a way of practicing autonomy and freedom but can also simply be observational. Many of us rediscovered this simple, free and yet essential act of walking during lockdown, and with it, relearned to pay attention to the outside world.

It can be a journey of discovery or investigation. “Walking is a mode of making the world as well as being in it,” Solnit writes. Done consciously, walking is a form of thinking, it is a means to creativity. It is an art form.

Seventeenth century poet Matsuo Basho, who gave the world haiku, was known as the ‘wandering poet’ because he would take month-long journeys throughout Japan in order to create his poetry. This practice was “meant to reach the very essence of things,” Thomas Heyd comments, but in a light way, highlighting everyday experiences.

In Europe, Jean-Jacques Rousseau made walking a ‘conscious cultural act’ and said his mind only worked when his legs worked too. Many other writers and artists developed their art form, or found inspiration, through the act of walking or wandering, from Charles Baudelaire to Walter Benjamin with the flâneur, to Virginia Woolf and James Joyce’s stream of consciousness.

But walking is also a way of connecting with history and ancestral knowledge. Indigenous communities in Australia and North America have been using navigational tracks called songlines as far back as 60,000 years. Songlines are like narratives about the landscape that would teach those walking about stories of their ancestors, from laws, art, the land, the stars, to warning about potential dangers along the road. One would have to memorise the songline in order to walk a particular path.

Beyond staying healthy and clear minded, what can we learn from those artists and ancestors and their relationship with walking? Solnit says walking “allows us to be in our bodies and in the world without being made busy by them.”

When we walk, we create rhythm: we might think or be lost in thought, we might daydream, remember or forget. It also invites us to pay better attention to what is around us because both body and mind are working together. In company, walking might enable far more intentional conversations than when sitting across from someone in a meeting room. It might make us feel vulnerable to others or to nature, but in turn, it can help us better understand our place in the world, and think more creatively about our responsibility towards it.

A static body leads to a static mind and in the words of Rebecca Solnit, “the fight against this collapse of imagination and engagement may be as important as the battles for political freedom, because only by recuperating a sense of inherent power can we begin to resist both oppressions and the erosion of the vital body in action.”

Words, Veronica Yates, illustration, Miriam Sugranyes

Visit our website for references and other resources.