Archimedes: ”Give me a place to stand and I shall move the earth.”

Chinua Achebe: “But such a place does not exist. We all have to stand on the earth itself and go with her at her pace.”

‘I am lost’ and ‘I don’t know’ are not usually states we aspire to acknowledge. From a young age, we are programmed to collect experiences and seek to know where we are, where we stand and where we want to go.

Yet traditional forms of knowledge – and of knowing – no longer hold the same reverence they once did and it seems increasingly that it is the appearance of knowing that matters more nowadays. Failing that, our phones are always only a few clicks away from any answer we may wish to find (sometimes even ahead of us), and they always know where we are.

However we have reached a point where our plans, strategies and certainties have blinded us and made us unprepared for what lies ahead. If we let these go, are we not more likely to become truly curious and see with new eyes?

For Socrates, who famously said “I know that I don’t know,” the most virtuous form of intelligence was not about having answers, but having the capacity to realise uncertainty. This was not a celebration of ignorance: one can only reach the state of ‘knowing we don’t know’ through proper investigation.

This is a space of questioning, but also, where we let go of seeking answers and solutions and see lostness as a place of openness, of wonder; a place where we can be, differently.

In A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit invites us to leave the door open to the unknown because that is where the most important things come from, “that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you is usually what you need to find, and finding it is a matter of getting lost,” she writes, “never to get lost is not to live.”

So how can we get lost and be at home in the unknown?

Unfortunately, getting lost, consciously, is not something many of us choose and is certainly rarely an option for children today who rarely roam, even within safe places. Yet, as Solnit writes, “childhood roaming was what developed self-reliance, a sense of direction and adventure, imagination, a will to explore, to be able to get a little lost and then figure out the way back.”

In a world of hyper-visibility, getting lost, even for adults, is a challenge and perhaps even a radical act. And according to Walter Benjamin, it requires schooling.

Perhaps we can start by stepping out of the binary view of lost/found and knowledge/ignorance and consider another dimension: one where lost becomes a place of inquiry.

Bayo Akomolafe says we have to enact lostness and escape the white modernity and globalising civilization that is like a monolithic enterprise, a single highway we are trapped in and which leads to nowhere interesting.

So we have to seek other forms of unknowing. “We are experiencing the toxicity of being fully found, fully owned, fully categorised, fully in place. … Constantly needing, insisting on naming everything, including violently. Something slips away when it is named. Including humility,” he says.

According to a Yoruba saying, to find our way, we must become lost. So lostness might be an invitation to creating new things, having different conversations, meeting differently, creating a new language. We need to “break out of the familiar into the exquisite, into the unthought, unto new ways of speaking and knowing,” Akomolafe says.

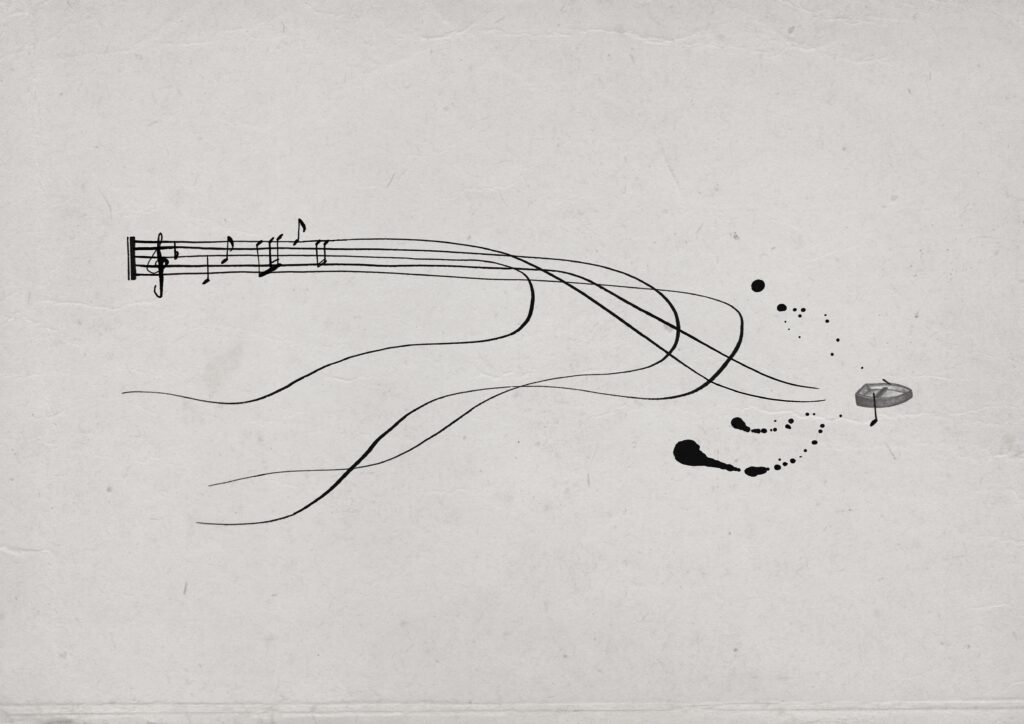

We here at the Rights Studio, are frankly, a bit lost. But it is a lostness we have sought and are dwelling in. The path we are taking is not linear, it’s exploratory, it is one paved with new questions about how to work, how to live and how to collaborate with others, and with art as the wind in our sails.

If you too are seeking different questions, whether about how to act in the face of climate collapse, or how we may change our approach to work, please get in touch as we’d like to organise a series of intimate conversations, where answers and solutions are not welcome.

In the words of Solnit: “To navigate life today, we definitely need new maps. Our old ones confuse us unendingly. These new maps are waiting for us. They’ll appear as soon as we quiet down and, with other lost companions, relax into the unfamiliarity of this new place, sense open, curious rather than afraid.”

See also: Seeing With New Eyes, The Art of Questioning, Living the Questions

For references and further resources, visit our inspiration page.

If you’re interested in this conversation, please send us an email at: info@rights-studio.org, with the subject line: Lost, Not Found.

Words Veronica Yates and illustration, Miriam Sugranyes