“Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

— Albert Einstein

In a recent paper called The Imaginary Crisis, Geoff Mulgan suggests that imagination matters because we all need a range of ideas to help us adjust to big challenges, like climate change and ageing. This means we need to be able to imagine and design different social arrangements.

But he argues we are suffering a deficit of social imagination as we struggle to picture a desirable or even possible future, leading to the general malaise around the world and “sense of lost agency and deepening fear for the future.”

There are many reasons for this – from the rise of individualistic cultures; the stronger pull of rationality and science edging out the space for imagination and intuition; and shifts in power, all of which have weakened “vehicles for collective action,” Mulgan explains. So we might be able to imagine a different life or future for ourselves, but not for society as a whole. But these concerns are not new. Einstein spoke of the crisis of the imagination, as did Toni Morrison and many others since.

I wish I could say, ‘it’s okay, let’s look to children’ as their imagination is often less restricted by rationality, but that too, seems to be slowly eroding. In 1997, political scientist, Giovanni Sartori, raised concerns about television’s impact on children in particular, saying if “children no longer have the capacity for abstraction, and if the thing is not seen or ‘seeable’, they are not interested to understand, so that’s a total guillotine on thinking.”

Research in the United States suggests that creative thinking is declining, especially among children in kindergarten, according to Mulgan. Think back to lego’s early days when we were just given coloured bricks and a few characters. Now, however, many games ask children to get from A to B, to build what it says on the box (a preparation for Ikea furniture assembly?). Children are not invited to imagine their own path or build their own world, but to carefully follow instructions.

Writer and anthropologist, Amitav Ghosh says that the climate crisis is a crisis of the imagination, that we are unable, at the level of literature, history and politics, to grasp the scale and violence of climate change. Yet, “climate change is outrunning us,” he says.

Ghosh believes that fiction may be the best form through which we can imagine other forms of human existence. Unfortunately, stories about climate change tend to be classed as science-fiction; and “the message is essentially that writing about climate change on earth is like writing about little green men or space aliens.”

So how do we approach this work? In order to feed into social change, imaginative ideas need to be shared by many minds and become a part of collective intelligence.

Echoing Indigenous traditions, Mulgan argues that to do this work of social collective imagination, it’s important to find the right balance between the new and the old, so “not discarding the best of the past, but rather finding ways to conserve the most resonant traditions, the fertile rather than sterile heritages, and combining them with the new.”

A Manifesto on Moral Imaginations states that “cognitive science is beginning to undermine the view that our sense making and meaning making happens by rational thought and deduction alone” and that “we need a new rigour, and that is a rigour of feeling, to change systems and culture we must feel differently, and not just change the map of where we want to go.”

Launched during the early days of the Covid pandemic, they invite people to work with metaphors to guide collective sense making and exploration of hopes, fears, visions, possibilities and memories to build collective imaginary worlds.

But it cannot simply be an activity we do every once in a while. It requires practice, it is, in fact, an art form.

Can we solve some of the world’s most pressing problems by training our imagination? Perhaps initiatives like the Little Inventors is one way to start.

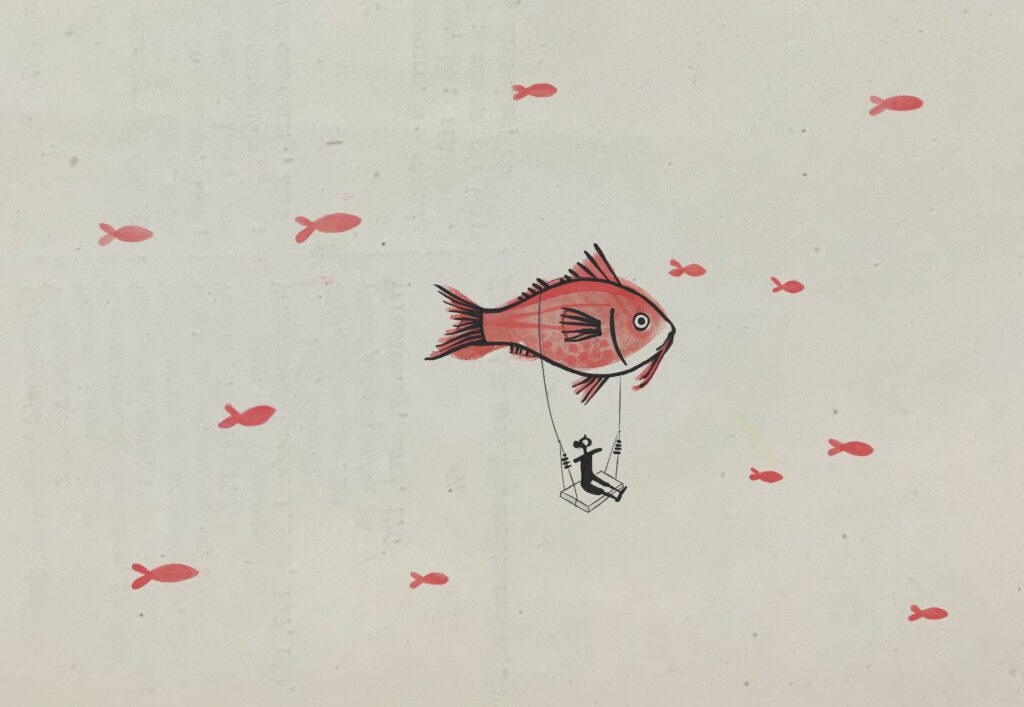

Words by Veronica Yates and illustration by Miriam Sugranyes