“Knowing that life is short and the task great, I let things go and I choose my work over polemics.”

— Auguste Rodin

A few weeks ago we shared our intention to exercise simplicity in everything we do. This would inevitably begin with identifying and removing everything that isn’t necessary. What if that included everything we do for show?

We all have a performative self: the things we do or say to make ourselves look good, appear happy or successful, whether in conversation or on social media – everyone of us does it to some extent, whether consciously or unconsciously.

But not all of it is a personal choice. Our society as a whole has taken transparency to such an extreme that it’s no longer about freedom, but about control. While it has a positive core, it has become absolute: we are increasingly compelled to be transparent about everything in our lives.

This is what Philosopher Byung-Chun Han refers to as the tyranny of visibility; where calls for transparency have taken us into a post-privacy world and everything that does not submit to visibility becomes suspect. In this way, he says, transparency leads to uniformity, compulsive conformity and eliminates Otherness.

“If everything becomes public right away,” Han writes, “politics invariably grows short of breath; it becomes short term and thins out into mere chatter.” Furthermore, total transparency “makes slow, long term planning impossible. A vision directed toward the future proves more and more difficult to obtain.”

This compulsion to be transparent, coupled with social media is also increasingly blurring the line between the private and the professional, turning our lives into performative busy-ness.

According to a NY Times article, young people are affected by what they refer to as performative workaholism where not only do they work excessively long hours (and sometimes live where they work) but they are also supposed to love work – and love it publicly.

A recent article in The Economist magazine suggests that performative work is on the increase. And it’s not just about employees wanting to be seen to work hard, but that so-called white-collar professionals are drawn to a kind of busy-ness which “neither overwhelms them nor leaves them with much time to think. Rushing from meeting to meeting, triaging emails and hitting a succession of small deadlines can deliver a buzz, even if nothing much is actually being achieved. The performance is what counts.”

Of course, performative work is not just the purview of us individuals, the private sector is a champion of corporate performatism, whether it’s fair trade, fair labour, diversity, or recently, climate pledges. While many of these initiatives come from NGOs or the United Nations and are well intentioned, they often end up serving more as a PR exercise for the corporations, rather than changing the underlying issues causing the violence and destruction it was intended to prevent.

A report by the New Climate Institute and Carbon Market Watch, for example, has highlighted that the integrity of climate pledges made by 25 of the largest multinational corporations, mostly amounts to greenwashing. The majority of them “are avoiding meaningful climate action and are instead using false, misleading or ambiguous green claims,” the report shows.

Those of us in the NGO or activist spaces are of course not immune. Whether we are compelled to show how clued in we are about every injustice we see, or whether it is to show our existing or potential donors that we are deserving of their funding, we are constantly required to perform.

This also relates to the growing phenomenon known as performative activism, also called slacktivism. This is a form of activism where all that matters is that we are seen to be supporting – or are outraged by – an issue or cause. Many such claims were made in light of the Black Lives Matter protests and the black squares on instagram, but also with government initiatives such as designating days of celebration of Indigenous Peoples, without changing any of the underlying injustices.

What is often the case, is that the important and hard work that needs to be done, is sadly not the ‘sexy’ work we want to be seen to be doing. And while there is value in highlighting greatness over mediocrity, when everything is put on display as worthy of celebration, it all just becomes noise. And the more noise there is, the harder it gets to discern a great idea worth pursuing or investing in over a mediocre one.

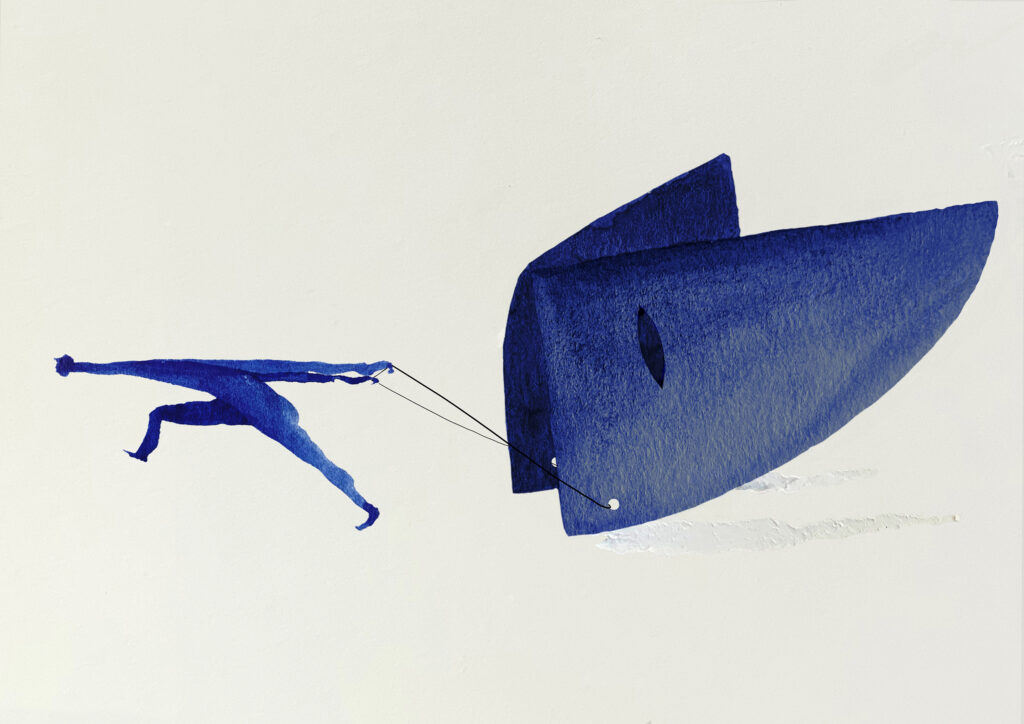

So what would we do if we had no audience to play to, or no one to report to? A true artist, for example, would do their work regardless of what people might think, or whether it might ever be shown publicly. Perhaps if we free ourselves from the performative, we could embody our work in the spirit of ‘dance as if nobody’s watching’?

Words, Veronica Yates and illustration, Miriam Sugranyes

For references, resources and further reading, visit our inspiration page.

Thank you for your insightful observations. I am teaching a college course called “Understanding Violence”. One section of the course deals with “Dehumanization” and one section of that section deals with “phony culture” as described by James Combs in his 1994 book, Phony Culture. Your insights about the contemporary world update this work. This takes on added importance for a generation for whom the world you describe is the NORMAL since they have known no other. (See this report from UNICEF detailing findings from a cross generational a survey comparing younger and older folks views and experiences:

https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/media/2266/file/UNICEF-Global-Insight-Gallup-Changing-Childhood-Survey-Report-English-2021.pdf

The sections relating to technology and social media, etc are incredibly important in conjunction with your observations!

Thank you again!!