“Any intelligent fool can make things bigger, more complex, and more violent. It takes a touch of genius – and a lot of courage to move the opposite direction.”

— E. F. Schumacher

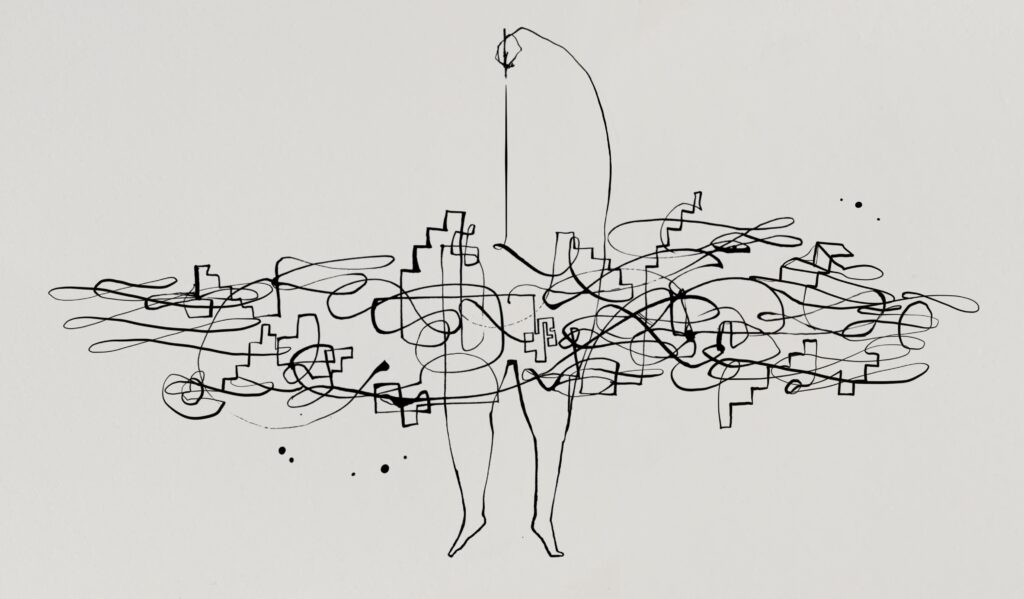

We begin this year and this second series with an exploration and an invitation to exercise simplicity, in all we do.

A new year is a time when many of us make resolutions, set new goals, perhaps we revisit broken commitments, re-examine our jobs, careers, relationships; perhaps we want to change our behaviours or declutter our homes. In our work and organisations, it’s often a time of annual planning, strategic reviews and fresh ideas.

Despite our good intentions, however, what often happens is we add more to an already overburdened life, job or system.

Lao Tzu said he had “just three things to teach: simplicity, patience, compassion.” For the Stoic philosophers, simplicity was one of the cornerstones of their teachings; simplicity and humility. The point was to live one’s life by getting rid of everything that was unnecessary. And H.D. Thoreau said our “life is frittered away by detail. Simplify, simplify.”

If we look to the world of design, architecture, music, poetry, games, the martial arts, even food, simplicity is sophistication; it’s an art form. But when it comes to our work, organisations or institutions, simplicity is most often distrusted or dismissed as naive, idealistic, even unprofessional.

It’s not all of our own making, however. We are living in a world that bombards us with too much information and endless bureaucracy. Many of us are increasingly feeling overwhelmed by the sheer magnitude of suffering we are witnessing; yet every cause or crisis demands our well-formed opinion and participation. As a result we struggle to make decisions and feel inefficient and exhausted.

So could simplicity become a practice we bring into our life and work? Perhaps we can start by understanding simplicity as a form of liberation. The late Thich Nhat Hanh spoke of ‘deep simplicity’ as a path to freedom, not just from our over-scheduled lives, but freedom “from hatred, despair, jealousy, and infatuation; freedom from getting so carried away by our work and busy-ness that we no longer have time to enjoy life or take care of each other.”

Of course, simplicity should not be understood as the opposite of complexity. Rather simplicity is where we arrive when we are able to navigate complexity, act and make decisions with discernment, and communicate with clarity.

Practising simplicity in the world of NGOs or large institutions unfortunately requires us to rebel. Everything we want to do asks us to fill out more forms, write new policies, amass more experience, present more ideas, achieve more outcomes. But how much of that could we actually do without?

In practical terms, we could start by differentiating between what needs to be simplified from an aesthetic point of view, for example, our language, messages, design; and what needs to be simplified through understanding, clarity and discernment, like our goals, strategies and procedures.

The former asks us to declutter, delete, erase; this one is really simple: it’s just about making the decision to do it. The latter asks us to dive deeper and identify and focus on the essential. This requires openness and humility.

For this, the people at the School of Life remind us we should “be sophisticated enough not to reject a truth because it sounds like something we already know. We need to be mature enough to bend down and pick up governing ideas in their simplest guises. We need to remain open to vast truths that can be stated in the language of a child.”

If we were able to apply this kind of thinking to our work, it might mean we no longer choose a course of action simply because we know how to do it or because someone is willing to fund it, but because it is what the situation requires.

In a recent conversation among activists about how to choose the right action in our complex world, Margaret Wheatley told us it was really quite simple. All we need to ask ourselves is: “what is possible; and who’s with us?”

Words, Veronica Yates and illustration, Miriam Sugranyes

For references, resources and further reading, visit our inspiration page.