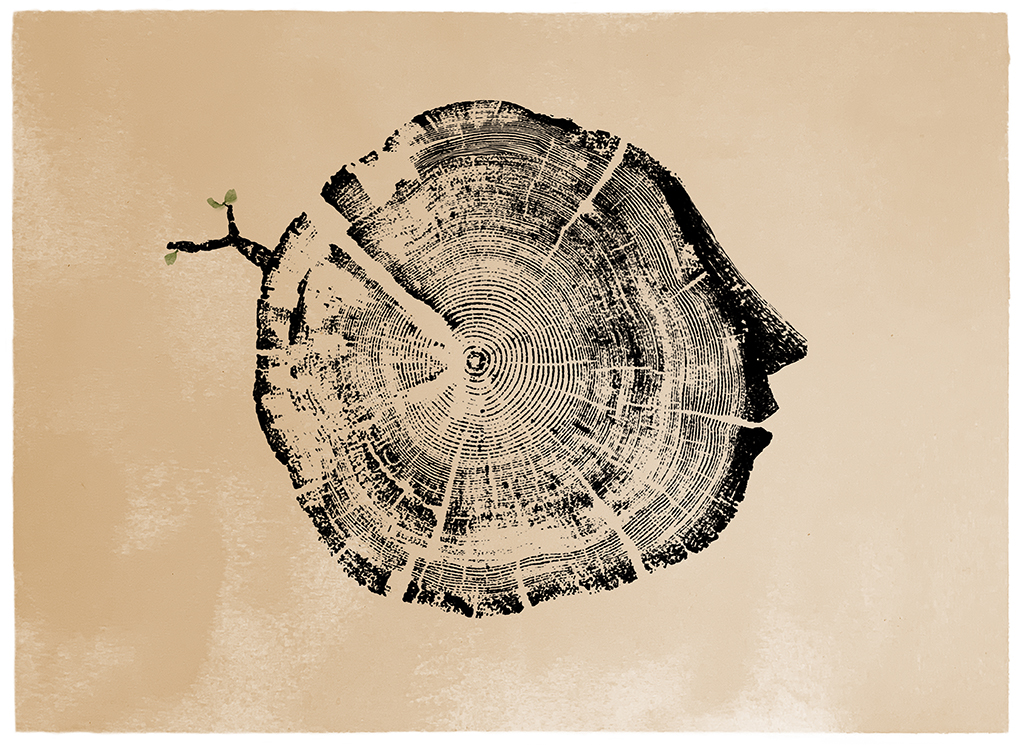

“The human interactions with trees and the forest are deeply embedded in our collective unconscious and cultural narratives, providing many of the fundamentals of our belief systems, folklore and endlessly inspiring literature and art.”

— John Tebbs

What can we learn from trees and forests?

Trees play a crucial role in the planet’s health, and by extension our own health, hence why we often refer to forests as the lungs of the earth. We also know that proximity to trees and green spaces have many benefits: from improving children’s healthy development, to better mental health and longer life expectancy for everyone.

They have many uses: we cut the wood for fuel, we build homes, boats and furniture, we make our pencils and paper out of them. But they also provide us with food, a place for children to climb, hide, build cabins in. They can be dark and scary or filled with light and wonder. They are an escape, a hiding place, a place of worship. They sometimes even look human, their branches stretching outwards and upwards like arms and hands. They hold many of our own personal stories and memories and inspire fairy tales, folklore and entire belief systems.

Yet there is a paradox: according to the United Nations, forests, like mountains and oceans, play a critical role in the balance of world climate (as well as in vital carbon capture and retention) and thus our survival depends on them, yet we are cutting them down at an alarming rate.

It might seem like an easy problem to solve: plant more trees. And there are plenty of initiatives proposing just that. But are we not yet again seeking redemption through quick solutions? In the past, we thought that sponsoring a child by giving to a charity was a good way to tackle poverty; now our latest magic bullet is to ‘plant a tree.’ However, such short termist solutions don’t fix the initial problem. They usually create new ones.

According to Nature, despite all the pledges and good intentions by governments, two-thirds of the areas committed to global reforestation for carbon storage have been allocated to grow crops, including 45 percent of monoculture trees. These do not do the job of storing sufficient carbon to alleviate climate change, but natural forests can.

So, can we shift our approach and perspective? Beyond needing to protect trees for our survival and that of other species, we can find inspiration and learn from how they live.

Up until recently, there was a belief that trees, like humans, were competitive – not just with other tree species, but even within their own. Recent research has revealed that this is, in fact, not true.

Writer Amitav Ghosh says that we now know that trees are connected and forests have ways of thinking, yet “we think we have the power because we can chop down the tree, but trees, if they think, think very much longer term, so maybe they are gardening us.”

We also know that trees communicate, organise and collaborate, both intergenerationally and with other species, like fungi, for example. In fact, it is the diversity within forests that is crucial for their wellbeing, development and problem solving.

Vandana Shiva says everything she needs to know she has learned from the forest and that the forest is a unity in its diversity, and it is this diversity that is the basis of ecological sustainability and democracy. “[D]iversity without unity becomes the source of conflict and contest. Unity without diversity becomes the ground for external control. This is true of both nature and culture.”

We can draw parallels with human rights being interdependent and indivisible, meaning that the realisation (or violation) of one set of rights affects that of others. But we struggle to approach our human rights work this way. Perhaps a way for us to break out of our silos or single-issue focus, or even the belief that we are competing for rights for one group over another, would be to think more like trees.

In The Nation of Plants, Stefano Mancuso states that unlike animals, plants see, hear, breathe and think with their whole bodies, meaning that they act in a distributed way, without a command and control centre. Us humans, on the other hand, function from a place of concentration, where we place primary importance on the brain. This has led us to create institutions and organisations that are hierarchical and bureaucratic.

So can we change our relationship to trees? Perhaps we can aspire to practice ‘forestness’ as a value, like the Mbuti people of the Ituri forest of north-eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, for whom trees are regarded as the source of their existence; their god, parent and sanctuary.

It is about the need to shift from anthropocentrism to ecocentrism, to turn to nature to learn of true freedom. As Vandana Shiva says, “[t]he forest teaches us union and compassion. The forest also teaches us enoughness: as a principle of equity, how to enjoy the gifts of nature without exploitation and accumulation.”

Words, Veronica Yates and illustration, Miriam Sugranyes

For references, resources and further reading, visit our inspiration page.